Best remembered as Scarlett O’Hara of Gone with the Wind, Vivien Leigh remains a defining figure in cinema and theater. Known for her grace, exquisite beauty, and effortless charm, she was an equally capable actress with iconic roles and versatile performances. The American Film Institute ranked her 16th among the 25 greatest female stars.

Her exceptional acting prowess earned her two Academy Awards for Best Actress. First for her unforgettable portrayals of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939) and second for Blanche DuBois in the film adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). She also won a Tony Award for her role in the musical version of Tovarich (1963).

People think that if you look fairly reasonable, you can’t possibly act, and as I only care about acting, I think beauty can be a great handicap.

Vivien Leigh

Early Life and Education

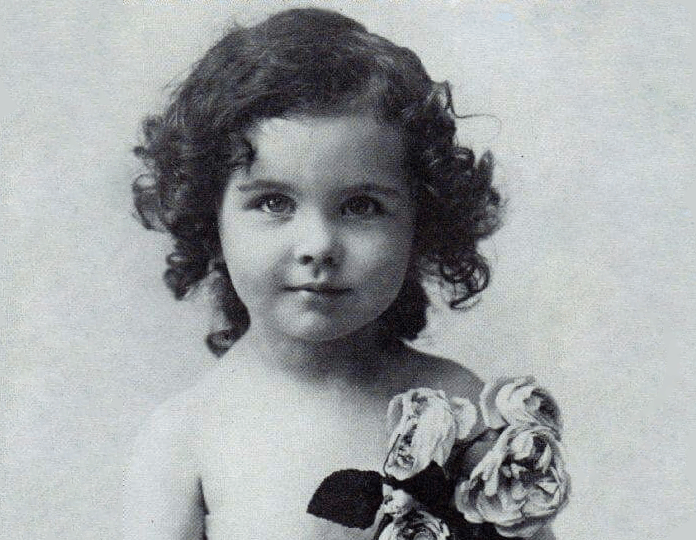

Vivien Leigh was born Vivian Mary Hartley on November 5, 1913, in Darjeeling, India. Her father, Ernest Richard Hartley, born in Scotland, worked as a stockbroker. Her mother, Gertrude Mary Francis Yackjee, had Indian, Armenian and Irish ancestry. Vivien was their only child. The family lived a comfortable colonial life until Leigh was six, when they moved to England due to World War I. She had twin sisters who died shortly after birth. Vivien grew up in a privileged household, often traveling between India and England.

Vivien attended the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Roehampton, England, starting at age six. She formed a close bond with Maureen O’Sullivan, who later inspired her acting ambitions. She later studied at schools in France, Italy, and Germany as her family traveled. In 1932, she enrolled at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London, though her progress there was modest. She trained there briefly before leaving to pursue acting professionally.

The Humble Start

Vivien’s career began on stage in 1935. She debuted in the play “The Green Sash” at age 21. That year, she adopted the stage name Vivien Leigh from her first husband, Leigh Holman. Impressed by her acting in “The Green Sash,” Sydney Carroll cast her in the play The Mask of Virtue (1935), which got her excellent reviews.

She made her screen debut with a small role in Albert de Courville’s “Things Are Looking Up (1935),” which led to a contract with Alexander Korda. Her early roles included small parts in British “quota quickies,” paving the way for larger opportunities. It was the time she met Laurence Olivier. Her breakthrough came in 1937 with Laurence Olivier “Fire Over England,” alongside Flora Robson and Laurence Olivier.

The film’s success caught Hollywood’s attention. In 1938, she starred in A Yank at Oxford (1938), with Robert Taylor, Lionel Barrymore and Maureen and Sidewalks of London (1938), with Charles Laughton.

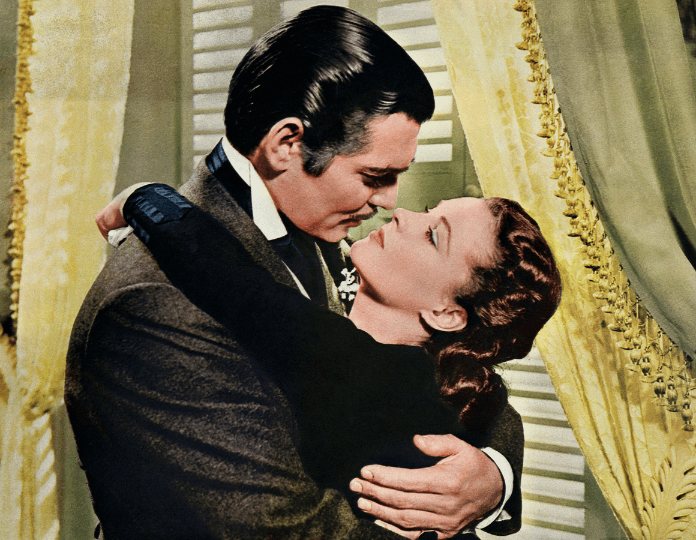

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Vivien Leigh’s life changed when she got the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939), a pivotal moment in her career. The role required a meticulous selection process overseen by producer David O. Selznick. Selznick launched a nationwide talent search in 1936 to find Scarlett, inspired by Margaret Mitchell’s novel. He tested over 1,400 actresses, including established stars like Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn. The process involved screen tests, auditions, and public speculation, with the role becoming Hollywood’s most sought-after prize. Initial favorites included Paulette Goddard, but Selznick sought a fresh face with the right blend of beauty and grit.

Quest For The Role Of Scarlett O’Hara

Leigh first heard of the role in 1938 through Laurence Olivier, who was filming in America. Olivier’s agent, Myron Selznick, David’s brother, mentioned the ongoing search. Leigh, already a rising stage actress in London, expressed interest despite her limited film experience.

Leigh arrived in Los Angeles in December 1938 to support Olivier during Wuthering Heights (1939) filming. On December 10, the night of the Gone with the Wind burning-of-Atlanta scene shoot, Myron brought her to the set. David Selznick met her under the dramatic glow of the fire, later noting her striking appearance and poise. Leigh’s green eyes and delicate features matched Scarlett’s description, sparking immediate interest.

Selznick arranged a screen test the next day, directed by George Cukor. She wore a green dress, echoing Scarlett’s vibrant spirit, and delivered lines with a mix of defiance and charm. The test, featuring a scene with Leslie Howard (Ashley Wilkes), impressed Selznick with her natural intensity. Cukor, initially hesitant, endorsed her after seeing her potential.

Scarlett O’Hara Personification

Selznick faced pressure to cast an American actress due to public demand. Leigh’s British origin raised concerns, but her performance silenced critics. Myron Selznick negotiated her contract, securing a $25,000 salary—modest compared to others’ offers. Studio heads debated her lack of star power, but Selznick’s conviction prevailed, finalized by late December 1938. Her casting announcement on January 13, 1939, ended the two-year search.

Leigh spent months preparing, working with a dialect coach and studying Civil War history. She collaborated with costume designer Walter Plunkett to shape Scarlett’s look. Her effort paid off, as she won her a Best Actress Oscar.

Leigh’s portrayal of Scarlett O’Hara, the resilient Southern belle in Victor Fleming’s epic, stands as her defining role. She navigates love, loss, and survival during the Civil War, balancing charm with defiance. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised Leigh’s portrayal of Scarlett as “a triumph of personality and skill,” noting her ability to dominate the screen. The role launched her into global stardom, proving her selection a masterstroke.

Further Acclaim

In Mervyn LeRoy’s wartime romance, Waterloo Bridge (1940), Leigh plays Myra, a ballerina in love with a soldier, Roy, played by Robert Taylor. The circumstances after the news of Roy’s death led to her becoming a prostitute. When Roy returned alive and wanted to marry her, even though she knew her reality, she committed suicide to save his honor. Her performance blends extraordinary charm and grace with heartbreak and despair. Roger Ebert, in a retrospective, credited her performance as Myra, one with “a quiet intensity that lingers.”

In 1941, she starred in Alexander Korda’s historical drama That Hamilton Woman (1941). In the film, she portrayed Emma Hamilton, a dancer, actressl and courtesan who at one point was one of the most famous women in England. Laurence Olivier portrayed the celebrated war hero Lord Nelson, her lover. Leigh’s poised yet tragic depiction of a woman rising from obscurity to influence earned immense critical acclaim. It was Winston Churchill’s favorite film. Leigh’s poised yet tragic depiction earned critical nods.

She was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1944 and spent most of the year recovering. She starred in Gabriel Pascal Caesar and Cleopatra (1945) opposite Claude Rains. It was the time she had a miscarriage, which led to her acute depression. The period of deep depression resulted in hysterical fits before everything went normal. Although she had experienced episodes of depression since her 20s, this incident was the most significant.

She also acted in Basil Dean’s 21 Days (1940) with Laurence Olivier and Leslie Banks. The film was an adaptation of John Galsworthy’s play The First and the Last. In 1948, she starred in Julien Duvivier’s “Anna Karenina” with Ralph Richardson and Kieron Moore.

Vivien Leigh On Stage

Vivien Leigh, although celebrated for her film roles, built a robust stage career that showcased her theatrical prowess. After the success of The Green Sash and The Mask of Virtue, she acted in plays like Richard II and Henry VIII. In 1937, Leigh toured with Because We Must and The Happy Hypocrite across Britain. Leigh played Ophelia in the Old Vic Theatre production of Hamlet opposite Olivier, her first with him.

Her stage presence grew, drawing comparisons to established actresses. She collaborated with Laurence Olivier, her future husband, in productions like Romeo and Juliet (1940), The Skin of Our Teeth (1945), and Richard III. Leigh and Olivier joined the Old Vic Theatre Company in 1948, performing Shakespearean classics. She played Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra and Lady Teazle in The School for Scandal.

Leigh was cast as Blanche DuBois in the West End stage production A Streetcar Named Desire (1949) with Laurence Oliver. Tennessee Williams’s famous play has many controversial and disturbing elements. She portrayed Blanche’s vulnerability and descent into madness with utmost sincerity and believability.

A Streetcar Named Desire

In 1951, Elia Kazan adapted the play A Streetcar Named Desire, to the screen. Leigh plays Blanche DuBois, the fading Southern aristocrat descending into madness, with Marlon Brando as the morally ambiguous Stanley. Her performance captures Blanche’s vulnerability and delusion, culminating in a sanitarium commitment. She drew from her own struggle with chronic depression and bipolar experiences, adding authenticity.

The role won her a second Best Actress Oscar. Pauline Kael lauded her Blanche in The New Yorker, calling it “a study in controlled hysteria,” highlighting her psychological depth.

Struggle with Depression and Bipolar Tendencies

Vivien Leigh faced significant challenges with depression and bipolar tendencies throughout her life. Leigh exhibited signs of mental problems from her twenties. Doctors noted mood swings as early as the 1940s, with episodes of mania and depression. A formal bipolar disorder diagnosis emerged in the 1950s, though terms like “manic-depressive psychosis” were used then. Her condition likely stemmed from genetic factors and stress, exacerbated by her demanding career and personal upheavals.

Leigh’s mental health strained her marriages.

Her first husband, Leigh Holman, faced her unpredictable behavior, leading to their 1940 divorce. Her second marriage to Laurence Olivier, endured 20 years of tension. Olivier documented her manic episodes, including a 1953 breakdown during Elephant Walk, where she hallucinated. Her collapse on Elephant Walk led to her replacement by Elizabeth Taylor, halting a major role. She relied on sedatives, impacting focus, as seen in The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1961). Despite this, she delivered standout performances, like Blanche DuBois, drawing from her experiences.

Leigh underwent electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and 1960s to manage mania and depression. She took lithium and barbiturates, though side effects like memory loss emerged. Merivale and doctors monitored her closely, adjusting treatments. Her reliance on these methods allowed periodic returns to work, but long-term health declined.

Later Work

Leigh’s condition did not derail her entirely. Despite health challenges, Leigh continued performing on stage. In 1953 she acted in The Sleeping Prince, Twelfth Night, Macbeth and Titus Andronicus with Oliver. She appeared in The Reluctant Debutante (1955) in London and toured with Duel of Angels (1960) in the U.S.

She won a Tony Award for Tovarich (1963) despite health issues, showcasing resilience. Her final stage role was in Ivanov (1966) at the Shubert Theatre, directed by John Gielgud. The production faced delays due to her tuberculosis, but she completed it before her death.

In 1955, she starred in Anatole Litvak’s The Deep Blue Sea with Kenneth More. Years later she acted in José Quintero’s The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone opposite Warren Beatty. Leigh plays Mary, a bitter divorcee on a doomed voyage in Stanley Kramer’s ensemble drama Ship of Fools (1965). Her late-career roles showcase aging and loneliness, marking a shift from her youthful leads. Critics noted her understated power despite health challenges. Vincent Canby of The New York Times found her performance as Mary Treadwell “a late-career revelation,” despite her frail health.

Her Craft

Leigh approached acting with meticulous preparation and emotional immersion. She studied Southern accents for Gone with the Wind, spending weeks with a dialect coach. For A Streetcar Named Desire, she observed mental health patients, channeling her bipolar episodes into Blanche’s fragility. Her process involved physical transformation—losing weight for Blanche and adopting period mannerisms for Emma Hamilton.

She relied on rehearsals, often clashing with directors to refine scenes, as seen with Kazan. Kazan, who initially believed “she had a small talent.” He later said that she showed “the greatest determination to excel of any actress I’ve known. She’d have crawled over broken glass if she thought it would help her performance.”

Her theater background, honed at RADA and with Olivier, emphasized voice control and stage presence, which she adapted for film. Critics admire her ability to blend naturalism with theatrical flair, a skill refined through stage tours.

Personal Life

Vivien married Herbert Leigh Holman, a barrister, in 1932 at age 19. They had a daughter, Suzanne Holman, born in 1933. The marriage ended in 1940, though they remained on good terms. Suzanne married Robin Farrington in 1957, had three sons, and died in 2015.

Vivien began a relationship with Laurence Olivier in 1937 while filming “Fire Over England.” They married in 1940 after both divorced their spouses. Their partnership, both personal and professional, lasted until their divorce in 1960. Vivien had no children with Olivier, though she suffered two miscarriages during their marriage.

In later life, Leigh faced worsening bipolar disorder and tuberculosis. In 1960, she began a relationship with actor Jack Merivale, who remained her partner until her death. Her daughter, Suzanne, grew distant, citing Leigh’s instability as her disorder disrupted family stability.

In her later years, Vivien lived in London, focusing on stage work despite declining health. Her tuberculosis worsened, leading to frequent hospital stays. Vivien passed away on July 8, 1967, at age 53, in her London home from a tuberculosis-related lung hemorrhage. Her body was cremated, and her ashes were scattered on the lake at her Tickerage Mill estate in Sussex. West End lights were dimmed for an hour in tribute.

Vivien Leigh on IMDB

Leave feedback about this