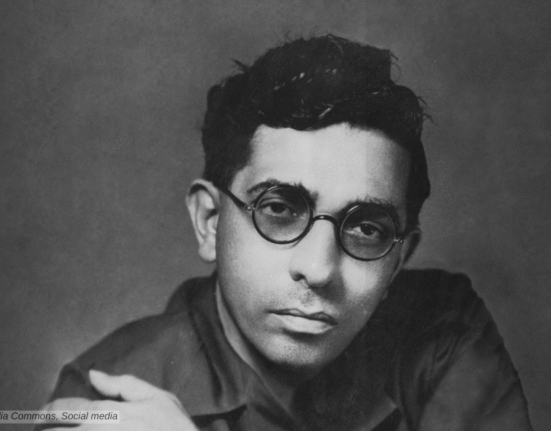

Marlon Brando wasn’t just an actor; he was a seismic force, a performer who reshaped Hollywood with a raw, visceral style that still echoes through cinema today. Known for his brooding intensity and groundbreaking performances, he brought a new kind of authenticity to the screen, blending vulnerability with defiance. It’s fascinating to watch how he could command a scene with a whisper or a glance, making you feel every ounce of his character’s soul.

I don’t think that people generally realize what the motion picture industry has done to the American Indian, as a matter of fact, all ethnic groups. All minorities. All non-whites. People just simply don’t realize. They take it for granted that that’s the way people are going to be presented and that these cliches are just going to be perpetuated.

Marlon Brando

Birth and Early Life

Marlon Brando Jr. came into the world on April 3, 1924, in Omaha, Nebraska. He was born to Marlon Brando Sr, a pesticide salesman, and Dorothy Julia “Dodie” Pennebaker, an aspiring actress and theater enthusiast. The middle child between sisters Jocelyn and Frances, Brando grew up in a household teetering between creativity and chaos. His mother’s love for the stage planted early seeds, while his father’s cold discipline fueled a simmering rebellion. The family moved to Evanston, Illinois, then Libertyville. Young Marlon spent his early days roaming farms and fields, a free spirit with a knack for mischief.

Life at home was rocky. Both parents battled alcoholism, and Brando Sr.’s harshness left scars—Marlon later called him “a mean son of a bitch”. Dodie’s warmth offered some refuge, but her drinking bouts were a constant struggle for her and for her young children. A childhood stutter didn’t help, though he turned it into a mimicry game, impersonating voices to cope. That restlessness, that edge—it was all there from the start, brewing in a kid.

Education and Training

Marlon Brando attended Libertyville High School, where his antics, such as riding a motorcycle through the halls, got him expelled. His father shipped him off to Shattuck Military Academy in Minnesota to discipline him, but it didn’t. Brando clashed with authorities, staging pranks like ringing the bell tower at odd hours. He was booted in his senior year of 1943. No diploma, no regrets—he headed to New York at 19, chasing something bigger.

There, he enrolled at the New School’s Dramatic Workshop under Stella Adler, a disciple of Stanislavski. Adler introduced him to the “Stanislavski system of acting”, which became the foundation of his craft. Her “Method” teachings—acting from the inside out—clicked with him, unlocking a craft he’d wield like a weapon. Brando’s stage debut came in 1944 with the play “I Remember Mama”, a modest success. He followed it with a few more plays like A Flag is Born, Candida, The Eagle Has Two Heads and Truckline Café, without much success.

The Arrival of Marlon Brando

It was Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” in 1947 that lit the fuse. At 23, he auditioned for director Elia Kazan as Stanley Kowalski—a brute with a tender core—and landed it after hitchhiking to Provincetown to read. His portrayal of a rough-edged, working-class husband with a mean and brutal bend of mind blended animalistic bravado with subtle vulnerability—his “Stella!” yell is still remembered for its emotional intensity.

Hollywood beckoned, and in 1950, he debuted in “The Men“, playing a paraplegic vet with a quiet fury honed at a VA hospital. The film flopped, but Brando’s star was born—gritty, real, and unapologetic.

In 1951, he reprised the role of Stanley Kowalski in the film adaptation of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” opposite Vivien Leigh and Kim Hunter. In the film, his raw, shirt-ripping intensity stunned audiences; critic Pauline Kael later said he “changed acting forever.” The film earned him his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, with critics noting how his physicality and improvised mumbles broke from theatrical norms.

Making Of A Legend

In 1952, “Viva Zapata!’ (1952) cast him as a Mexican revolutionary, another Kazan gem that nabbed a Best Actor nomination. He famously played Mark Antony in “Julius Caesar” in 1953. In the film he shows his Shakespearean chops and delivers the iconic Caesar’s will speech, “Friends, Romans, countrymen …”

One of his other memorable roles came with László Benedek’s “The Wild One (1953),” where he played the motorcycle gang member Johnny Strabler. In the film he rode his own Triumph Thunderbird 6T motorcycle. The role made him a cultural icon of the 1950s. He became the role model for teen rebellion for the emerging rock-and-roll generation. Brando’s look in the film as a leather-jacket-clad biker became the definition of cool, which led to the sales of leather jackets and motorcycles skyrocketing.

Despite having serious differences with Elia Kazan, he starred in his film “On the Waterfront” in 1954. He played Terry Malloy, a dockworker turned whistleblower, in the film. His delivery of “I coulda been a contender” in a cab scene with Rod Steiger—partly improvised—stands as a masterclass in understated power. In film, his portrayal of Terry Malloy’s struggle with moral choices and his path toward redemption earned Brando his first Oscar.

Brando’s filmography consists of over 40 films, spanning pans, triumphs and tangents. Some of his other standout films include Guys and Dolls (1955), The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), Sayonara (1957), The Young Lions (1958), The Fugitive Kind (1960), One-Eyed Jacks (1961), Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), The Ugly American (1963), The Chase (1966), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), Candy (1968), Burn! (1969), The Nightcomers (1971), and Superman (1978), among others.

The Comeback

After a not-so-successful decade, Brando collaborated with Francis Ford Coppola for “The Godfather (1972)“. He redefined the mob boss archetype when he portrayed Don Vito Corleone in the adaptation of Mario Puzo’s novel. At 47, he transformed into an aging don with cotton-stuffed cheeks and a raspy voice, a choice born from a DIY audition tape after Paramount resisted his casting. His quiet menace—think the opening “offer he can’t refuse”—earned a second Oscar, which he famously rejected to protest Native American portrayals.

The same year came Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris (1972),” which saw Brando as Paul, a grieving American in a raw, sexually charged affair with Maria Schneider. Filmed in Paris, the film became a big success amid controversy over its explicitness and earned him another Oscar nomination. Brando drew from his own life—his mother’s alcoholism, his father’s coldness—for unscripted monologues, like the one by his dead wife’s body.

The Faulty Genius

One of his most controversial and impactful roles came in Coppola’s Vietnam War epic “Apocalypse Now (1979),” as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz. The film is remembered as much for Brando’s unprofessionalism and moody behaviour as for its brilliant portrayal. Playing a rogue officer gone mad, he improvised much of his dialogue in a 17-minute cameo, filmed in shadow to mask his 300-pound frame—a far cry from the lean figure Coppola expected. Brando’s hypnotic, philosophical descent into madness is a masterclass of acting. His chilling whisper of Kurtz’s final words, “The horror! The horror!”, has since become legendary.

In 1980, after the failure of John G. Avildsen’s “The Formula,” based on a novel by Steve Shagan, he took a sabbatical from acting. He made a comeback in 1989 with “A Dry White Season,” directed by Euzhan Palcy. The film was based on the anti-apartheid novel by André Brink. Despite having a fallout with the director, his performance was widely acclaimed. He was even nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

Some of his later films are known for getting absolutely scathing reviews, like Christopher Columbus: The Discovery (1992), The Island of Dr. Moreau and Free Money (1998). In 1990 he starred in “The Freshman (1990),” where he did a caricature of the famous role of Vito Corleone. He acted with Johnny Depp in Jeremy Leven’s “Don Juan DeMarco in 1995. He again collaborated with Depp in his controversial directorial “The Brave (1997).” His last film was “The Score (2001), where he acted alongside De Niro.

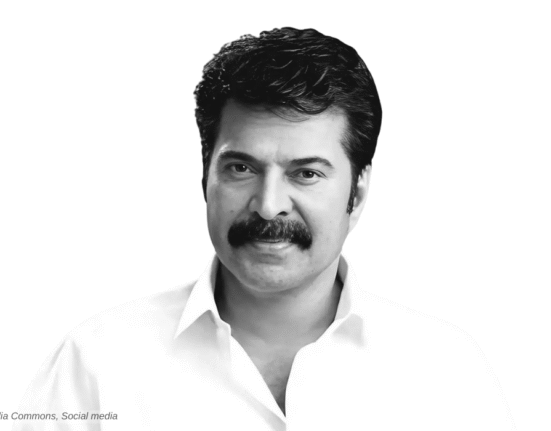

Marlon Brando The Statesman

Brando’s life was a storm. His 1973 Oscar rejection for “The Godfather”—sending Sacheen Littlefeather to protest Native American treatment—is still one of the boldest and most daring gestures ever made on the issue by a celebrity.

The caste system may be more highly developed in countries like India or England, but every tier of society in almost every culture tries to dominate a group it perceives as beneath it.

Marlon Brando

Brando was a rebel with causes. A vocal civil rights advocate, he marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 and funded the Black Panthers. His Native American activism—backing the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation—stemmed from guilt over Hollywood’s portrayals. He flouted norms—showing up late, rewriting lines, and clashing with powerful filmmakers and studios. That daring made him magnetic but divisive; he once called acting “a bum’s life” yet poured himself into it.

Personal Life

Marlon Brando’s love life was a saga—three marriages, countless affairs, and at least 11 kids. He wed Anna Kashfi in 1957 and had the son Christian in 1958. The couple divorced in 1959 amid legal battles over the custody of the child.

In 1960 he married Movita Castaneda and fathered son Miko and daughter Rebecca. They separated in 1968. Tarita Teriipaia, his “Mutiny” co-star, married him in 1962 and had Teihotu and Cheyenne. They split in 1972. Affairs with Rita Moreno, Maria Schneider, and others bore kids like Ninna (1989) and Timothy (1994). He lived with housekeeper Maria Cristina Ruiz from 1988, adding three more—Petra, Maimiti, and Raiatua.

In 1991, his son Christian killed Dag Drollet, boyfriend of his daughter Cheyenne, in a drunken row. Christian was sentenced to six years. Cheyenne’s 1995 suicide at 25 broke Brando further.

Later years saw him retreat to Mulholland Drive, ballooning to 300 pounds, grappling with debt and grief. He died July 1, 2004, at 80, of respiratory failure from pulmonary fibrosis at UCLA Medical Centre. Cremated, his ashes split between Tetiaroa and Death Valley—a final act of enigma.

Marlon Brando didn’t just act—he rewrote the rules. From Streetcar’s howl to Godfather’s murmur, he gave us truth in every frame. His politics ruffled feathers, and his daring cost him roles, but that’s what made him Brando. At 80, he left us—a flawed giant whose shadow still looms, a reminder that greatness doesn’t play it safe.

Marlon Brando on IMDB

Leave feedback about this